- Extra Innings Festival Announces Lineup: Tempe AZ, Feb. 28 and March 1, 2025

- Ella Langley is Fabulous at Two Step Inn: Review and Photos

- Rob Zombie’s Freaks on Parade Tour: Review and Photos

- Vlad Holiday, with photos: The Eclectic Sound of Modern Melancholy

- Opinion: Alexander Morris, member of the Motown group The Four Tops, files lawsuit against Hospital ER for use of “straightjacket”

- Dave Matthews Band has a grand slam at the Extra Innings Festival in Tempe, Arizona

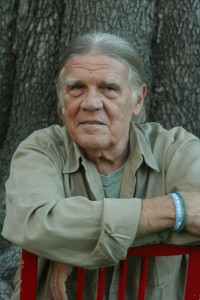

Seeing Stuff with Photographer Henry Diltz

Some storytellers communicate with their words, others through their music. Henry Diltz tells a story by capturing the fleeting dance of what his eye sees as his finger presses the shutter button on his camera. A moment in time artfully preserved, and forever shaping how that moment is remembered.

Some storytellers communicate with their words, others through their music. Henry Diltz tells a story by capturing the fleeting dance of what his eye sees as his finger presses the shutter button on his camera. A moment in time artfully preserved, and forever shaping how that moment is remembered.

Starting out as a musician with the Modern Folk Quartet, fate played a hand in his eventual career path. While on the road with the band Henry bought a used camera and the rest, well let’s just say the history of the musical world would be a little different today had Henry Diltz not found his true calling.

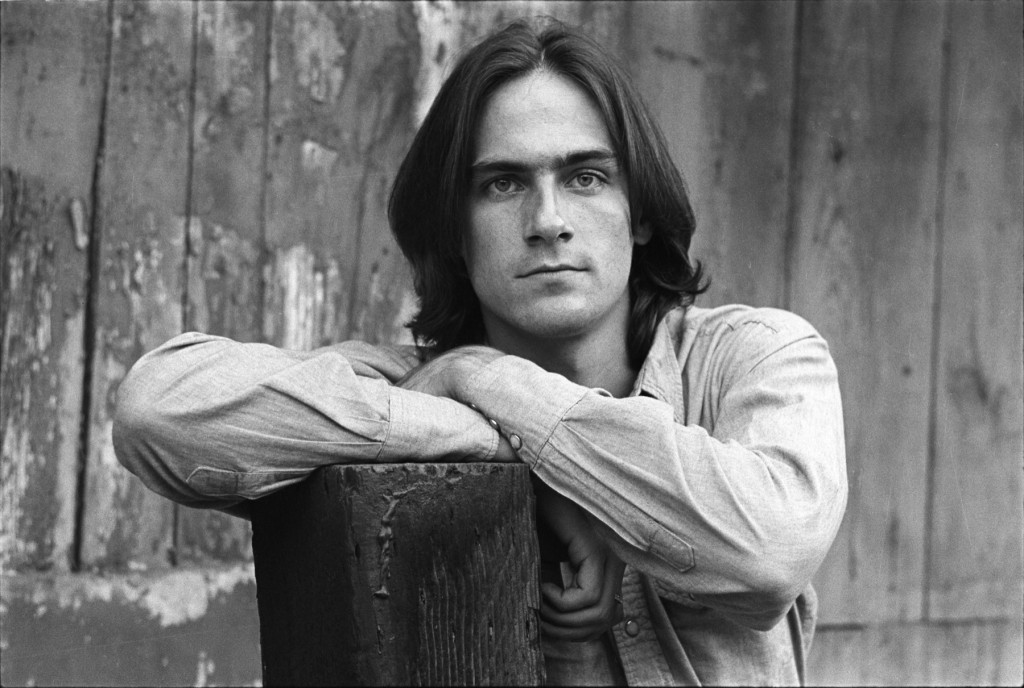

Slideshows became a weekly ritual for his friends and neighbors whose names included some of the most important singer-songwriters of the era: The Mamas and the Papas, Joni Mitchell, Frank Zappa, Stephen Stills and many others. He took pictures of his friends, and eventually created some of the most unforgettable album covers of all time. James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James, the first album from Crosby, Stills & Nash, The Doors Morrison Hotel, Late for the Sky by Jackson Browne. He documented the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, Woodstock in ’69, Woodstock ’94, and Woodstock ’99, creating a photographic statement of entire generations in musical history.

It is not an exaggeration to say he has photographed nearly everyone of musical importance in the last fifty years. With some partners, Diltz opened the Morrison Hotel Gallery (NYC and LA) where exhibits of his work and many other of today’s important photographers can be seen. Henry is taking some of his work on the road beginning next month as he and fellow photographer Pattie Boyd begin a limited run multi-media tour featuring historic photos and what no doubt will be extraordinary stories about them.

Having followed Henry’s work since I first became a teenager, it was beyond surreal to interview him. His life is fascinating and he is surely one of the coolest men on the planet, if not the universe. And Henry, thanks for the title.

Kath Galasso: Your first camera came from a second hand shop, you bought some film for it, took the photos, had it developed and only then learned it was slide film not print film. You then went on to have slide shows for your friends, and eventually that cycle was how you became a photographer. In the game called “what if?” do you think you would have become as interested in photography if you would have picked up developed prints rather than slides?

Henry Diltz: You know, I may not have become a photographer. I don’t say that I thought it would be prints, I had no idea what it would be. We bought these cameras at a junk store on the road and then one of the guys in the group said “pull into the next drugstore and I’ll get film.” He handed everyone a yellow box, I still didn’t know what it would turn out, I never even thought about it. I just said ok and then I said, well how do you set these numbers on the lens and on the camera and he said “look on the box.” Kodak just told you how to set it. Whatever it was I just set the camera that way and it worked out. And when I picked them up, I said “oh look, they’re little tiny pictures, they’re little slides.” And at that moment I said hey let’s get a slide projector and have a slide show. And that was the magic moment right then, actually when the first slide hit the wall, I went “oh my god.” These things could be twelve feet across and glimmering and shimmering in the light. If you have the right conditions in a dark room and your audience is all your stoned, hippie friends, it could be pretty intense. And before I really had a whole collection of music photos, before I got into that really, it was pictures of old junk trucks, pickup trucks, cats sleeping in the afternoon, snails on the ivy or mailboxes. I would just photograph everything and try to make it real interesting, the weirder the better. I wanted to get a response from people. That’s what I went for; to always get a reaction when the next slide hit the wall. And that was what propelled me into photography; I just wanted to have more slide shows.

But isn’t that the coolest thing that you could trace how your life turned out to that one moment?

Yes! I know, I know. I think about it, I think about it in many ways. One way is to say “hey life is a happy accident” you know… and then right away I have to think well, or maybe not. Maybe it’s not such an accident. Maybe my spirit guide or guardian angel said this is what you actually signed up to do, so we’re going to put a camera in your hand. You never know. When you live long enough and really think about life enough, you start to get some answers as to what life might really be, it gets very interesting.

You’ve said “back in the 60s, never once did I think ahead and think that I was capturing an era.” But that’s exactly what you did, and for a lot of us, you captured one of the most memorable times of our lives. In retrospect, can you even wrap your mind around the fact that you have influenced how the world views that specific time period?

I can, and I must say it’s in sort of a detached way. I was just having lunch with somebody and we went into a Coffee Bean and the guy behind the counter says “Are you Henry Diltz? oh my god.” And I said to my friend, it’s really nice when people do that, and I understand what they mean, ‘you took those great pictures and we love it,’ but I don’t take it personally. It’s kind of like a detached thing. It’s like I know I did that, it was my job somehow to do that, but they were events that happened and I got to push the button and try to save them. I feel honored and blessed that I got to do that. So that’s the first thought, the second thought is every day was another day, it was an adventure. I think life is an adventure, even today. But back then, in the 60s holy cow, what a fun time we had. And yeah, I never once thought one day I’m going to have all these pictures. It never occurred to me. I really just got to be the guy that stood there and got to experience it.

When you first started taking photos, they were of the musicians who were your friends, you weren’t an outsider, you were just “Henry with the camera.” You kind of continued that approach with other subjects by just hanging with them for a while, getting them comfortable before you started shooting. I can’t help thinking that approach created the naturalness in you photos.

It has, in the documentary part. What I really love to do is hang out with people and photograph what I see happening. Kind of like Jane Goodall with the chimpanzees. She would sit there and write and observe what was happening, but not want to interact at all because it would change what would happen. Same thing with me, I wanted to just hang out and observe and take photos of what was really happening because that was the most interesting part. Not ‘why don’t you guys go stand over against that wall and I’ll take your picture.’ Eventually when somebody says “hey we need a group shot,” then you have to do that. And the photography part is almost secondary to me, the main part is to be with people. I’ve always had a fascination with people, I was always interested in people. It’s a little bit like being a kid climbing under the circus tent and just standing there in awe.

One of the things I’ve always loved about your work is you relied on the subject, not props or even landscape, finding just the right moment to frame the picture, using simplicity as a rule rather than the exception. Can you see the picture in your mind’s eye or does it form as you look through the viewfinder?

It all happens at once. Yeah, that little tiny window you look through and there you see the world, and when you see that moment it’s almost instantaneous. You just push the button. It can be if someone’s on stage, say Neil Young is up on stage playing, and I’m squatting there in front of the front row, trying to keep down so I’m not blocking anyone’s view, and looking through a telephoto, and looking and looking and waiting until he turns the right way and the guitar’s just right and he opens his mouth and click. Bang, you just take it. Like watching The Monkees on their TV set, I would squat among the light stands with my camera trained on The Monkees. On either one of them or two of them or four of them, or whatever. It could have been a wide-angled scene or just one guy. You’re just ready for it, you just push the button. It’s the most fun of all. It’s observing people and catching them at that great moment, at the height of it. It happens all at once. There it is and before you can even say there it is, you’ve taken it.

How did you become the official photographer of Woodstock?

In the folk days, we did hundreds and hundreds of concerts. College concerts and folk clubs and one of the guys we met along the way was a fellow named Chip Monck (the announcer at Woodstock). His name was Edward Beresford Monck and his friends called him Chip. He was a lighting guy back then, then he became a staging guy. In early August, I’m in Laurel Canyon and I get a phone call from Chip Monck in New York. And he says “Henry, we’re gonna have a huge concert out here in a couple of weeks, you ought to be out here for it.” I said “Chip I’d love to but I don’t know any of those people. How am I gonna get into that?” He said “Well I’ll talk to the producer for you.” The next day Michael Lang (Co-Producer of Woodstock) called and said “Chip called and said we need you. I’m sending you a ticket on TWA and five hundred bucks.” And I flew out there, I spent two weeks documenting the whole setting up. It was building the stage, all the people in the office making phone calls, the Hog Farm setting up the camping areas, all the stuff that went on.

From your perspective behind the lens, on the stage, by the stage, looking out at the crowd, what is the thing that is the most memorable about Woodstock?

Well a couple of things. First of all I think we were all just overwhelmed by the sea of faces. No one had ever seen that many people in a crowd before. And to top it all off, the first afternoon somebody came in with a New York Times newspaper and the picture on the front page was an aerial photo. Then it was like “oh my god, we’re a part of history.” But even before that looking at the faces was amazing, in the early sunshine before it rained. And the thing was we’d all seen groups of hippies in our hometowns, and the love-ins and peace-ins, and be-ins in the park on Sunday, but it was like the gathering of the tribe. We didn’t realize that there were so many thousands of us.

You were always around musicians, were you also documenting them when they were writing songs?

I’d seen them. I’d seen John Sebastian in Greenwich Village in the summer of ’66 when I had first gotten the camera. He could only write songs with a pencil on a cardboard from a Chinese laundry. The shirt cardboard, and that’s how he wrote his songs. I’ve been to Stephen’s (Stills) house and seen his notebooks laying around with lots of words written. Always in pencil too and then scratched out with other words on top. I haven’t seen songwriters sit in the process that often. I’m fascinated with songwriters, how they do that. How they transfer what they see and feel into words and music that they can share with everybody. And how universal that usually is.

You took a photograph of the band America with Bob Hope and John Wayne. An unlikely combination of people to say the least. What was that all about?

America got booked to be musical guests on The Bob Hope TV Show and they filmed it at UCLA college here in LA and I was hanging out with them all the time, I was their photographer just like I was for The Monkees. So I went along and we were hanging out in the locker room and there was Bob Hope. They knew John Wayne was going to be on the show and they had these leather America jackets. They had one made for Bob Hope and they had one made for John Wayne. But they made it huge because he’s bigger than life. So he put the jacket on and the sleeves were about a foot too long and he had to push them up. It was way bigger than John Wayne was. I think it was a jacket for his aura. So they put them on and I just documented the moment. Most of my pictures aren’t a set up thing. No one said “hey we’re going to put these jackets on and you take the picture.” They just put the jackets on and I was there to take it.

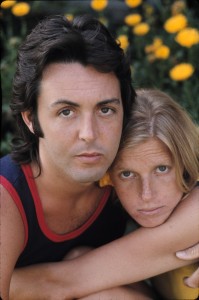

Tell me about the photos you took of Paul and Linda McCartney, when she had asked you to come out and photograph them.

Tell me about the photos you took of Paul and Linda McCartney, when she had asked you to come out and photograph them.

I had met her in New York City in a photo lab, we were fellow photographers and I got to know her long before she ever met Paul. Some years later I was amazed to see my old friend married to Paul McCartney. She called me one day in LA and said “We’re out in Malibu, can you come out. We need some photos of the two of us for a songbook.” They just did the Ram album together. So I went out there and spent the day photographing the two of them around the pool and outside. We had lunch, and the two little daughters were there, I just documented the afternoon and then we took some portraits of the two of them. Then Linda said “We want to see these first thing in the morning because we want to pick one out for the cover of Life Magazine.” And I said “Wow, are you kidding me?” So they picked one out and they had the lady from Life Magazine waiting in the living room. They handed her the one slide, she put it in her purse, drove to LAX and flew to New York with it, because back then in ’71 we certainly had no FEDEX and we certainly didn’t have any scanning or emailing. We didn’t even have fax machines. So the quickest way to get it there was to hand carry it on the plane. So that became the cover of Life Magazine.

You’ve said being a photographer is like having a passport into other people’s lives.

It certainly is. I mean all the people that I’ve hung out with, like why would I be hanging out with Keith Richards or Paul McCartney for that matter. I always use that phrase in conjunction with Truman Capote. Rolling Stone called and asked if I could fly to Truman Capote’s house in Palm Springs and take the picture for the cover of Rolling Stone, which I did. But I just thought, wow, there’s a guy I had read about in college, we read his short stories. I never knew that I’d be at his house with him, taking his picture. That was fantastic. It is a passport into people’s lives because otherwise why would you be there spending the afternoon in the midst of somebody’s life? They need a picture and you’re there to take it. I love that. Like I said before, for me the picture is secondary. The people make it for me, getting to hang out, get close to people and observe them.

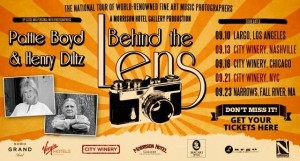

You’re taking your photography on the road, tell me about the “Behind the Lens” Tour.

Pattie Boyd and I are doing this slideshow tour. It’s kind of like a documentary, but it’s live. We’re going to be showing all these pictures and telling all the stories behind them. It’s going to be a great pleasure to do this. This will be the first time that we’ve actually taken it public on the road. I’ll do my slide show then we’ll have an intermission and Pattie Boyd will come out and do her slide show. And my partner in the gallery, Peter Blachley sent me the video opening that he put together for Pattie Boyd. It made me cry, it absolutely made me cry. So beautiful, with the songs written about her, the videos of her in A Hard Day’s Night, kissing George, Eric talking about her. It’s just fantastic.

Morrison Hotel Gallery Website

Interview by Kath Galasso @KatsTheory

Pingback: Woodstock 1969 – OnStage Magazine.com

Pingback: Behind the Lens with Henry Diltz and Pattie Boyd - OnStage Magazine.com