- Opinion: Alexander Morris, member of the Motown group The Four Tops, files lawsuit against Hospital ER for use of “straightjacket”

- Dave Matthews Band has a grand slam at the Extra Innings Festival in Tempe, Arizona

- Sheryl Crow brings the heat to the Extra Innings festival in Tempe, Arizona

- Backstory: Kenny Loggins’ “Heart to Heart”

- Chris Isaak’s Almost Christmas Tour: A Rockin’ Holiday Treat

- P!nk’s Trustfall Tour: A High-Flying Spectacle of Rock and Soul

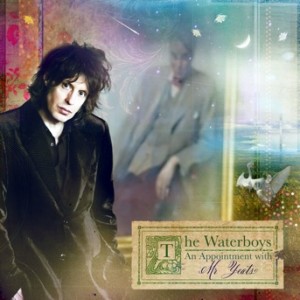

One-on-One with The Waterboys’ Mike Scott

In 1923, the committee for the Nobel Prize in Literature described recipient Irish poet William Butler Yeats as a writer of “inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation.” The same can be argued analogously about The Waterboys’ landmark 1988 album Fisherman’s Blues, which earned a similar reverence in Ireland (and subsequently beyond) as a piece of work that reflected the essence of that country’s traditional music roots and also the embracement of newer genres.

Yeats and Waterboys visionary Mike Scott share a parallel desire to employ those faithful, ancient, traditional elements in their art while at the same time forging ahead and pushing their respective mediums in unpredictable directions. Therefore, the initially galling idea to take the revered lyrical works of Yeats and turn them into rock and roll is tempered when the name “Mike Scott” enters the picture.

Scott’s first collaboration (so to speak) with Yeats, “The Stolen Child,” appears as the closing song on Fisherman’s Blues. It is an evocative treatment, rendered in an alternating spoken-word and singing style. The song’s warm acceptance by fans set the stage for Scott to eventually pursue the creation of a full Yeats album. The result, two decades later, is An Appointment with Mr. Yeats. Scott and the rest of The Waterboys channel all genres of music to create the necessary landscape conducive to the thriving of Yeats’ original, implicit rhythms and rhymes.

In addition to this new album, Scott is working on a box set of unreleased material from the Fisherman’s Blues sessions, which spanned several years and countries in its creation. It is called Fisherman’s Box, and it’s set for an October 2013 release. I had a chance to speak on the phone with him earlier this week, as he prepares for some North American dates this summer and fall in support of An Appointment with Mr. Yeats and in anticipation of the box set.

In the spirit of telling a complete narrative here, I must give a prelude about what happened just prior to the interview. It easily could have gone off the rails before it even started.

In the spirit of telling a complete narrative here, I must give a prelude about what happened just prior to the interview. It easily could have gone off the rails before it even started.

After organizing the interview with The Waterboys’ publicist, I was given customary instructions to call Mike’s home in Dublin at a specific day and time. So when the time came, I picked up the phone and dialed overseas. However, for some reason the number or code wouldn’t work; I kept getting a busy signal. I called the operator who gave me instructions that also didn’t work. So by the time I finally figured it out and got through to him, it was about 8-10 minutes past the prescribed interview time. More than a little rattled, I apologized to Mike, whose publicist (unbeknownst to me until after the interview) was sending me emails this whole time (“Call now please,” “We are standing by,” etc). Mike, in his delightful Scottish accent, cheerfully brushed off my tardiness (“oh no problem, Chris”). To add to the situation, however, my telephone recorder had gone on the blitz just before I made the call. Therefore, I had to record from the speaker of the phone into the external microphone of my laptop. I was afraid to tell Mike this for fear that he’d say, “I’d rather not be on a speaker phone,” so I carried on as if everything were normal. I’m sure it was anything but normal for him as the interview proceeded, because the speaker phone is just not an ideal way to speak seriously and intently with someone about his/her art. But alas I was left with no choice.

I’ve included the ensuing glitches and interruptions in italics for the comedic element. It does help set off the dead seriousness of the subject of Yeats, although I don’t know if Mike would see it quite this way. Although maybe he would. He seems to have a keen sense of humor. Anyway, I digress. Here is our conversation.

Chris: How far back does your fascination with Yeats go?

Mike: My mother is an English lecturer, so I remember her talking about Yeats as a kid. So I grew up with an image of this great arch-poet, whom I’d never read. When I was 11 my mother took me to the Yeats country in the West of Ireland, so I then had a landscape to go with the name. And then when I was in my teens I found a very slim book on my mother’s bookshelf containing a poem called [at this point I move the speaker phone by accident, and it sounds like a big guttural moan]…whoops…are you still there? [I say yes and apologize]…called “News for the Delphic Oracle,” which I didn’t understand but I loved it, and I loved the description of Pan [mythological figure] in the third verse. And then, many years later when I was a Waterboy touring Ireland, I saw a book of Yeats’ in a shop and bought it. So that’s when my serious appreciation of Yeats began and I first set it to music a few years after that.

Chris: Your own lyrics seem informed to a certain extent by Yeats, especially in its natural and mystical themes. Has Yeats been a major influence on you as a songwriter?

Mike: Well…maybe. There’s a line in The Waterboys’ song “Old England” that goes, “You’re asking what makes me sigh now and what it is makes me shudder so.” [I laugh inappropriately here because I think he’s using a Yeats quote to make a joke about my question. But he’s not. So there’s a bit of an uncomfortable pause after my outburst. We carry on…tentatively.] Yes there must have been some influence on me because I love him so much. But I’m not sure I could quantify that.

Chris: Did your musical adaptation of Yeats’ “The Stolen Child” on Fisherman’s Blues inspire you to want to do a full album of these adaptations?

Mike: Well not immediately. At first I thought about compiling a record of various artists’ interpretation of Yeats, because I knew there had been one by [Irish singer] Christy Moore and another by Clannad, an Irish Band, and Bono had tried one that had never come out. So I thought, “maybe I could gather all these.” But I had so many other things to do, and gathering other artists into a compilation album isn’t really my forte. But over the years I’d set others of Yeats’ poems to music, just for pleasure. So I began to realize that one day I’d have enough of these myself for a stage show and an album.

Chris: Did you deliberately have to try to avoid the temptation to make this album all about traditional instruments and such? Some people no doubt associate Yeats with ancient themes, so the knee-jerk tendency is to picture this as a trad album, which is it certainly not.

Mike: Well I’m a rock and roller, Chris, so that was the starting point for me. [A moment of quiet here, no doubt due to the weird silence a speaker phone leaves between pauses.] Can you still hear me okay? [I tell him that I certainly can; I’m a bit mortified]. Good, good. When I’d approach each poem, I’d let the poem suggest the melody and I would take it from there. I didn’t have too many preconceptions that it should be this kind of music or that kind of music. But I will say that over the years I’d heard many interpretations of Yeats’ poems done very reverently, with harps and flutes and those trad-type instruments that you’re meaning. And I always felt that they were too obvious, and that it should be different. It should have a twist. Yeats himself was never an obvious writer; he was ahead of his time and he changed the game. So I figured when I set it to music I’d have to push the boat out.

Chris: Some tracks, such as “The Hosting of the Shee,” incorporate the sax which automatically harkens back to mid ‘80s Waterboys, or “the big sound” as its become known. What qualities do you think brass instruments bring to a rock setting, and why have they been a consistent sound in The Waterboys?

Mike: Well I think the sax is a fantastic rock and roll instrument, and I used to love Clarence Clemons’ sax solos on Springsteen records like “Jungle Land,” for example, and various others. And I knew that sax was a great solo instrument in the early days of rock and roll, so when I first heard [ex-Waterboys’ saxophonist] Anthony Thistlethwaite, I thought, “that’s the guy for me. I want him in the band.” And around this time, in the early ‘80s, brass instruments were very fashionable in British music. Every band has a trumpeter or a trombone player, or at least one horn player. So it was in the culture. And I asked Anthony if he knew a trumpeter who could come in and turn him in a section. He recommended Roddy Lorimar, and together they played on the early Waterboys records.

Chris: Regarding the October release of Fisherman’s Box, did you think at the time when you were tracking all over the UK and in North America that a lot of this would be released, or were you “barn burning” in your mind as you went?

Mike: Well any of it could have been released. Every time we recorded I knew that this could be on the record.

Chris: So you weren’t in demo mode.

Mike: We didn’t do demos. We just played. And I didn’t remix anything for the box set because the desk mixes from the night were always superb. We had a great engineer, so it all sounded great. It would spoil it to remix it, really.

Chris: I’m sure you credit the Fisherman’s Blues with putting you on the larger map in popular music, but do you ever feel like it has overshadowed some of your earlier and later work? Do you think that period is focused on too much regarding you as a songwriter?

Mike: No I don’t think so. It was an incredibly creative time for The Waterboys, and I’m happy that it still has a currency. The Fisherman’s Blues era was some of the best music we made, and think some of the albums since haven’t been as good as that. I don’t count Mr. Yeats; I think Mr. Yeats is a top-line Waterboys album, one of the top three or four we’ve ever made. But I do feel that some of the other albums were not as good as Fisherman’s Blues, so I think it’s fair.

Chris: You have some North American dates coming up in July, and a tour planned for October. Does this part of the world, especially America, hold any fascination for you? Bands like The Who, Led Zeppelin, and the Stones all cite this fascination with the culture and I guess its connection to the roots of modern music.

Mike: It does. I’ve listened to American music all my life, and I’ve loved it all my life. So it’s inspirational for me to go through American cities like Chicago, New York, L.A., San Francisco, and Austin where so much great music has been made and is still being made. And I love the visceral quality of the audiences in North America. I find the Canadian audience to be every bit as good as the USA audience.

Chris: Fisherman’s Blues was a particularly big hit in Canada when it came out, so I’m glad there’s a back and forth there in how you feel about Canadian audiences.

Mike: There have been a lot of Canadian covers of songs from that album, maybe ten versions of the song “Fisherman’s Blues” by different bands.

Chris: Yes, as my friend Bob Hallett in Great Big Sea once said, “it was the album that spawned a thousand pub bands.” Well, Mike, that’s great. I’ve gone through all my questions here. I don’t want to keep you any longer. I hope all the questions were okay for you.

Mike: Yeah, it was very enjoyable. Thank you.

Chris: Okay well thank you very much. I’ve got tickets to see you in July when you come, and I will be reviewing that show as well.

Mike: Great! Well I look forward to saying hello to you again.

Chris: Excellent, Mike. Safe travels when you come, and I will see you soon.

Mike: Thanks. Farewell!

(For more information about The Waterboys’ adventures, please click here )

0 comments