- Opinion: Alexander Morris, member of the Motown group The Four Tops, files lawsuit against Hospital ER for use of “straightjacket”

- Dave Matthews Band has a grand slam at the Extra Innings Festival in Tempe, Arizona

- Sheryl Crow brings the heat to the Extra Innings festival in Tempe, Arizona

- Backstory: Kenny Loggins’ “Heart to Heart”

- Chris Isaak’s Almost Christmas Tour: A Rockin’ Holiday Treat

- P!nk’s Trustfall Tour: A High-Flying Spectacle of Rock and Soul

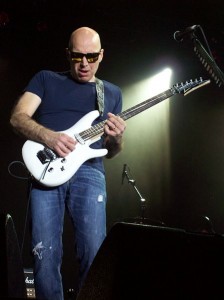

One-on-One with Guitar Virtuoso Joe Satriani

In the world of instrumental rock, the name Joe Satriani looms large. Cultivating a successful career as a headlining guitarist who doesn’t sing seems like a monumental task in the grand scheme of the music business, but Satriani has not only achieved this remarkable ambition – he has paved the way for others who also now enjoy the fruition of creative guitar-based songwriting as a viable genre in today’s competitive musical climate. Those experiencing success as instrumental guitarists today owe a lot to Satriani, who, along with Jeff Beck and a few select others, fearlessly blazed a trail decades ago both on stage and in the studio to bring “guitar-as-voice” to artistic and commercial success in the new millennium.

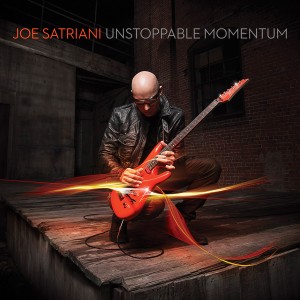

I caught up with Joe on the phone from his home in California as he prepares for an extensive fall tour to promote his latest solo album, Unstoppable Momentum. We talked about his time playing with Mick Jagger and Deep Purple, his role as teacher for some high-profile guitarists, his early musical interests, and his recent collaborative activity.

Chris: You’ve just released your 14th studio album, Unstoppable Momentum. I wanted to ask whether or not your experience in Chickenfoot collaborating with a vocalist [Sammy Hagar] changed your instrumental approach on this record. Was there any sort of influence there? Or was that coincidental? I hear a more chord-based approach on some of the main hooks on the new record.

Joe: One thing is for sure: whatever you do musically has an influence on what you do next. I think that applies to everything in life, so it would be silly for me to say that there was no effect. Since 2008 I’ve played with such a big variety of people. I made four albums, did a lot of guest appearances, went on a lot of G3’s, did Chickenfoot tours, did my own tours, generated two or three live concert films…all of that has had such a huge effect. Even if you just focus on the different bass players and drummers I’ve played with, and the experiences I had in the studio and onstage, it’s just kind of changed what I was excited about doing next. So I arrived late October last year, having done three G3 tours internationally and even did some Montrose tribute shows with Denny Carmassi, Bill Church, and Sammy. I really felt like, “Man I have played with a lot of people!” I’ve got all these influences of different grooves and different ways that people want to do things; even Sammy singing in two different ways with the Montrose stuff and the Chickenfoot stuff. I looked at about 60 songs I had, and I just sort of focused on 16 that I thought were making me feel good. I mean…I’d have to say yeah, there was some influence but I don’t know what it is. I think everything influenced me.

Chris: I noticed that you have legendary drummer Vinnie Colaiuta [Sting, Jeff Beck] playing on your new album.

Joe: Yeah Vinnie was fun to play with. I played with him once before a number of years ago at a Les Paul birthday party; we did a couple of songs. It was really a lot of fun, and then I ran into him on one or two Chickenfoot tours where we were on the same bill in Europe. So we were sort of connecting and thinking that we’ve got to play together again somehow. And as I was trying to think of ways to add challenging elements to the studio experience, I thought that maybe it was the time to call Vinnie and see if he’s available. In fact both Vinnie and Chris [Chaney, bassist] were available for just about eight to ten days in January, so I kind of pushed the button on that. I thought, “Okay I’ll just see if it works – if I’m ready for them, and if we can do it.” And it just turned out to be a wonderful experience. Every day was fun; it was exciting. The record took a turn that was different from the previous albums where I tried some different concepts. So it all wound up being a great choice, bringing Vinnie and Chris as new players into the mix.

Chris: Your musical cohort Steve Vai played with Vinnie in the Frank Zappa days, correct?

Joe: Yeah, that was a long time ago, but yes, they did. Vinnie is probably one of the most recorded drummers in history because he’s such a great session player. He’s been playing with Sting and Jeff Beck almost exclusively, as far as touring, in the last number of years. But he continually makes lot of records, if you go to his website you can see he’s pumping out a good number of records every year. It’s a wide variety: he’s doing pop, rock, blues, and experimental…he gets around.

Chris: Yeah I just saw him play with Sting a couple of months ago and he was quite a presence onstage; Sting was interacting with him a lot as a bass player, of course.

I have a question about your songwriting. Seeing that you primarily write instrumental music, I was always curious about when and how the title of the song comes to you. Does it come as a result of what you’re composing, or do you have a lyrical idea and then compose around that inspiration?

Joe: Just like any other classical or jazz composer of yesteryear, I get inspired about some thing, event, person, or interaction, and I write a song about it. So it’s direct, and usually I know exactly what I’m writing about as the first note becomes apparent. It’s really not that far-fetched. Western music has a long history of several hundred years of instrumental music based on themes, stories, and people. It’s never crossed my mind, I guess, because I grew up listening to classical and jazz, along with rock; it always seemed normal to me. I just don’t see what the difference is really, in terms of inspiration. If you watch your dog die in the middle of the street and you’re moved to write a song about it, is it weird that it’s an instrumental? I don’t think so. So falling in love, having a good cheeseburger…I don’t care what it is. You should be able to express it. So that’s how I do it. I know exactly what I’m writing about as I start. Every once in a while, about once in a hundred songs, it does a little flip where I think I’m writing it for Sammy and then it turns out to be an instrumental, or vice versa. But that rarely happens.

Chris: My father was a big fan of 60’s instrumentals growing up – artists like The Ventures and The Shadows – and I sort of grew an affinity for them as well. But since then, rock instrumentals have certainly evolved and you’ve obviously spearheaded that transition. Do you have any connection to those instrumental rock pioneers of the 50’s and 60’s?

Joe: Well, you know, as a young kid – the youngest of five kids – growing up in New York, I was hearing pop and rock radio all the time. So although I was really young when “Sleepwalk” came out, it stayed on the radio forever and I heard it probably before I knew who or how it was being played. Then there were other instrumentals that would pop up all the time on the radio. So I got used to that. I heard the surf music with Dick Dale, The Ventures, and The Shadows, later on Hendrix, and all the blues instrumentals. In the 70’s when I was starting to play guitar and gig, there were artists like Edgar Winter who had huge hits; one of them was “Frankenstein,” a big instrumental. I was listening to Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, and Jimmy Page…they all had instrumentals on their records. So to me it was always just part of it all. I always wrote instrumentals; I just didn’t think about releasing them until I was getting into my late twenties. Then it became just sort of a lark to experience starting my own record company and publishing company…and to see what it was like to try to self-market. All of a sudden, in 1988, I had a hit record and the record company asked me to go on tour – even though I had never played instrumental music as a solo artist onstage before. I literally started green at age 30. It was really quite an experience, I’d been playing in rock bands my whole life; I knew how to act like Jimmy Page behind a singer, but I did not know how to play rock instrumentals onstage – like how to act, how much to move, what kind of gear to use…none of that! Trial by fire, you know?

Chris: That same year you ended up on the road with Mick Jagger, didn’t you?

Joe: Yeah, that really helped because I started right in January of ’88 with my very first tour on the east coast with Stu Hamm, Jonathan Mover, and me. We had just met a few months earlier and played one show. So we were kind of winging it. The genre itself was not supported anywhere yet, so people didn’t know how to book us. We were playing small clubs two shows a night for about two weeks, I was already losing a lot of money per week, and I didn’t know how I was going to rectify that when I got home a week later. And out of the blue I got a call to come down to an audition for the Mick Jagger solo tour, which I didn’t even know was happening. I was in Boston at the time, I was heading to New York, I had four engagements at the Bottom Line and it turned out that Bill Graham was actually running Jagger’s tour. So when Jagger had gone through about 60 guitar players, and was still looking for somebody, I think Jagger’s bassist at the time, Doug Wimbish, had said, “Hey I know this guy Joe. Look he’s on the cover of Guitar Player Magazine! He’s a cool guy.” And then Mick said, “Okay, well we’ll bring him down.” So I got the call from the Bill Graham people who knew I was out on tour, and it really saved me in a number of ways. Number one was that my tour wasn’t going so well. Even though the record was charging up the charts, I had no history out there selling tickets. But of course meeting Mick was great. He exceeded my hopes and dreams as far as what a rock star should be like. He turned out to be a great musician and a fantastic entertainer. He just loved his audience and he did everything to put on a great show. He was funny to hang out with. He was interesting, generous…he did everything he could to help my career that entire year. It was really remarkable what he did for me; he gave me a solo spot in the middle of his show for the Japanese, Australian, New Zealand, and Indonesian tours. We remain good friends to this day.

Chris: Do you think that sort of generosity and spirit exists as much now between musicians? Back then it seemed to be more apparent, with major stars helping others forge music careers. Nowadays it seems to be a bit more hands-off and less organic than it used to be.

Joe: Yeah, I don’t know. I only know my own experience, and the people that I work with have always been good people. I’ve been very fortunate to be surrounded by people who always take the high ground. I’ve tried to do the same thing; therefore, I don’t seem to get exposed to that negative part. If I do, we always just go in the other direction. We don’t hang out with those people. My experience with Deep Purple was the same way, it was just an experience because they were great people and great musicians and there was great material to play.

Chris: How much woodshedding did you have to do for the Deep Purple material, such as “Highway Star” and other complex pieces? Not that they’re hard for you to play, but you must’ve had to put aside your own material for a bit and devote your time to learning those songs.

Joe: Yeah well I only had a week for the first tour; that was rough. The thing is that Ritchie is quite remarkable and quite unique, and I’m such a fan that I couldn’t get over the sound of him in my head. That was the hardest part. Physically it’s not the most difficult thing ever written; most accomplished players could physically do it, but nobody can do it like Ritchie. He can sound like Ritchie Blackmore playing it the right way a million different ways, because he wrote it. But the rest of us, all we do is copy this version or that version; we can’t help it. That’s the reality of true artistry; you can imitate one version or another, but you can never replace the original guy’s freaky, artistic approach.

Chris: Yeah I guess the hands dictate the tone, as opposed to what kind of guitar or amp the person is playing with.

Joe: You’re absolutely right. I think that’s what led me to eventually turn down the offer to join the band. I just kept thinking that I like Ritchie Blackmore but I don’t want to spend the rest of my life trying to replace him, because I know I can’t. I couldn’t help wondering what was going to happen to my sound; I couldn’t deal with that inner conflict. So I had to turn down the offer to become a permanent member.

Chris: That makes sense because you’d already forged your own sound, so it would almost be a step backward if you spent your time trying to imitate a sound of style different from your own. You got the best of both worlds because you got to experience it, yet you were able to continue on with your own original vision.

Joe: Exactly.

Chris: I’m a guitar player myself and I use one of your pedals, the Vox Time Machine. I find it very intuitive; it’s very easy to use. It’s got a mixture of analog old school settings and also the most modern tap tempo stuff you can get on a delay pedal. I think it’s very usable, and it sounds great too. When you were partnering with Vox, did you have a vision in your mind of usability mixed with versatility?

Joe: Yeah…I mean it came from years of struggling with pedals that I liked but would always lack some particular feature. I’d spent a good number of years using the Echoplex [tape delay] and then finally could just not take the degradation of sound from the beginning of the show to the end. They were noisy and they would break, and it was insane to try to keep those going. And the audience doesn’t want to watch someone struggling with a piece of gear, right? So I said, “Well I got to get this gear together so that it’s inspirational to the artist but it works; it always works. You step on it, you can do the things you need to do.” That’s why I thought a digital delay is important because if you’re playing five shows a week and you’re moving every single day, the Echoplex is out of the question. You need something small, you need to have a backup, it’s got to fit in a bag, it’s got to be readily available around the world, and then it’s got to have your general area of repeats. I think zero to two seconds is pretty damn good. And you know having the tap feature, having the EQ cut to more faithfully imitate the tape delay is great, I don’t think we went overboard. On some other pedals they go so totally vintage that it really becomes something of a one-trick pony. At some point you have to say, “if I put every trick into this thing it’ll be an $800 pedal.” So how do we keep it down so that normal guitar players can afford it? I think we’ve always tried to settle on two or three of the most important aspects of a guitar player’s gig. Whether he’s playing weddings, club dates, theatre shows, amphitheaters, stadiums, whatever. What does he really need that box to do? So we kind of put that into the Wah-Wah, the Time Machine, and into both the Saturator and the Ice 9.

Chris: Yeah they’re great pedals, very intuitive. I came across the delay about a year and a half ago and it’s been on board ever since.

Joe: Great.

Chris: You’ve taught some of the true guitar greats in music…hugely successful artists like Steve Vai and Kirk Hammett, for example. Do you ever hear your playing in their playing sometimes?

Joe: Not really. I think about some of my other students like Charlie Hunter, David Bryson, Kevin Cadogan, and Alex Skolnick; I don’t really hear myself in them at all. They’re so uniquely different. Steve and I spent the most amount of time together; we knew each other when we were teenagers and he was a beginner. Not only have we spent a lot of time where I’m teaching him guitar, but also as comrades jamming together. We grew up in the same town and we’ve toured together more than any other set of guitar players I can think of. So there’s definitely an area where we cross over. It can’t be helped.

When I was teaching Kirk he was still in Exodus in the beginning, and during the lessons he got the gig playing for Metallica. The biggest issue was that all the things he was able to play were rock and blues-based. How does that work in the song structure of a Metallica song? It was the hardest thing, because I was slightly older and wasn’t really in it like he was. He was the perfect age to experience that music and to feel it and create it. He had to make that decision. I would give him the raw materials: the theory, the scales, everything. But then I would say, “Well you’ve got to go out and you do it, because you’re Kirk Hammett. You’re the guy in Metallica. You’re the perfect age to make the decision of how to use these musical tools I’m showing you.” For me, I always hear their personality. Maybe it’s because I know them so well that I can identify with their personality.

Chris: It’s kind of like when a person takes art lessons. A good teacher can show a student exactly how to paint like them, but the sign of a great teacher is one who provides the student with basic techniques and leaves the creative vision up to them.

Joe: Well I hope I’ve done a good job.

Chris: Speaking of influences, on your latest record you have a pair of songs titled, “Jumpin’ In” and “Jumpin’ Out.” I’m hearing influences like David Gilmour and Jeff Beck on this set of tunes. Would that be accurate?

Joe: Well I think they’re all in me. You mentioned two outstanding musicians. They both play and write like crazy, and I think all musicians absorb anything they hear that’s good. Both Dave and Jeff are heroes of mine, and I wouldn’t be surprised if people pick up on that. But the songs themselves specifically for me are tied together because of their swing. That is a holdover from my youth, listening to my parent’s jazz collection and just loving all the different periods of swing from the ‘40s, ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s. Swing changed very much, and we could talk for hours about the technicality of swing and how people swing. How you can get one person in band to play straight and have the other person swing around it…the effect that it has on the audience is really remarkable. So part of what I was working on was the idea that sometimes you shouldn’t be afraid to jump in and try something different, and then sometimes things get so crazy you got to learn when to jump out. So I wrote those two songs basically around that, that sort of emotional, intellectual thought process, and then tapped into those influences that are part of my roots.

Chris: Well it’s very interesting how we can talk about 40’s jazz and how its style has evolved, yet the basic elements like time signatures and grooves are still there.

Joe: Yeah I’m a student of music still. I’m fascinated by music, and I’m still excited about it. I suppose that’s what the title of the album is all about, the continuing excitement I have for music and exploring.

Chris: Joe, it’s been a pleasure chatting. Best of luck with your fall tour!

Joe: Thanks, Chris. Hope to see you at a show. Bye!

0 comments